|

|

Intelligence isn’t spontaneous. Whether organic or artificial, it takes time and training to form—nature and nurture. But when it does emerge, what do we attribute it to? Is it the result of monumental effort, complex systems, and more than a bit of luck? Or is it just magic?

In his 1968 letter to Science magazine, Arthur C. Clarke wrote, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” We’re approaching that point with LLMs and AI today. Even though we know it’s not magic, it can be easy to forget that sometimes.

I got chills the first time I got a personalized, helpful answer from a self-hosted LLM using my data.

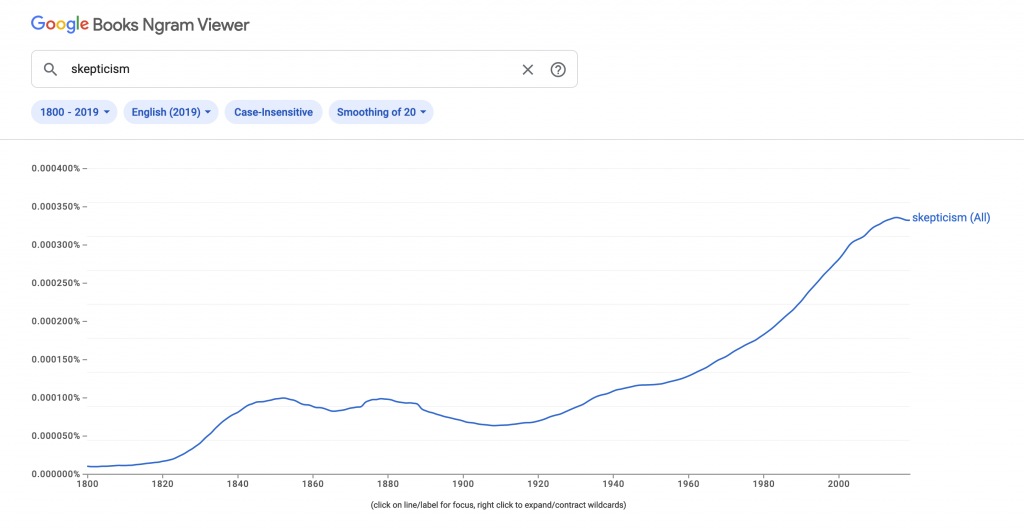

It’s easy to lose our healthy sense of doubt when we’re presented with new evidence of magic almost every day. Whether you ask Claude a question and get a helpful response, or you’ve just created an entire video from a simple text prompt with Sora, the tools and opportunities have rapidly extended beyond what many of us dreamed was possible, much less probable. Practical skepticism is a necessary counterbalance to the fantastic technology we’re surrounded by today.

Blind denial and blind faith both miss the mark

What is skepticism, though? When we think about definitions through opposites, the first thing that may come to mind is blind faith. In religion, we talk about the doubters and the believers, the skeptics and the devout. But skepticism isn’t a pole, it sits in the center.

The opposite of skepticism isn’t blind faith; it’s also blind denial. Both represent a choice we’ve made, intentional or by default, not to ask questions.

We don’t ask questions just to be contrarian, constantly on the defense, or because we’re scared that someone might pull one over on us. Instead, we should ask the hard questions and keep feeding our skepticism because it forces us to form an educated opinion—one that we are confident is our own because we spent the time interrogating the questions ourselves.

Society is built on trust, much of which we defer. We can’t broker independent relationships with each institution, scientific community, and government that we rely on daily. That’s ok! Imagine if we each tried to have a personal relationship with the people at the treatment plant that cleans our water. I know I’d rather spend my time on other things, and I think the people over there would rather not have to talk to me about the intricacies of the grades of charcoal and sand they use all day.

But that deferred trust was originally built on skepticism. Questions like, who was running the water department? What were they testing for? How did they safely sanitize the water? Outside of an elementary school field trip, you and I probably didn’t ask those questions directly. In all likelihood, neither did our parents. Look far enough back, though, and you’ll find someone who did.

It’s a tired cliche, but it’s true. We stand on the shoulders of giants. Everyone who came before us asked hard questions for our benefit so that we wouldn’t need to be quite as skeptical.

It’s our turn to take up the mantle and ask those hard questions for everyone who follows.

Question everything

Artificial Intelligence is poised to change the way our grandchildren interact with the world around them in ways we’re only starting to imagine. By the time it gets to them, it might seem as mundane as turning on a tap to get clean water is to many of us today.

That trust hasn’t been built yet.

First, we need to do some interrogation, teach the questions to ask, and demand explanations in exchange for trust. The questions we ask depend on the level of detail we personally need to make a reasoned decision.

Start with the basics:

- Who made this?

- Do I trust the company behind this technology?

- Do they have a track record of integrity and transparency?

- Why did they make it? Are they a for-profit company? Venture-backed? Who are the investors?

- What does this cost? If it’s “free,” how am I paying?

If you want to know more, ask deeper questions:

- Do I understand how this works at a high level? At least the steps involved, from compiling the dataset to pattern recognition to inference.

- Can I trust the integrity of the data this system was trained on?

- Do I even know what data this was trained on?

- How is the owner of this system thinking about safety and bias?

- Can I ever trust technology to act in my best interest?

Then go a little further:

- Is trust more than faith based on past behavior?

On being human

Awe makes us real. It puts us back on our heels and forces us to reflect, challenge our worldviews, and reframe the impossible into the probable. If we lose our ability to sit in wonder, whether at new technology that we didn’t see coming or something as “routine” as a sunrise, we surrender part of what it means to be human. Is there anything more human than harnessing that awe and turning it into rabid curiosity?

Terry Pratchett wrote that ninety percent of magic is knowing just one extra fact. Practical skepticism, not falling prey to blind denial or blind faith, gives us a chance to learn that one extra fact.